“I have seen an original 1611 King James Version. I cannot read it. It looks like a foreign language.”

These and similar words roll off the tongues of otherwise intelligent people who do not appreciate and often even oppose the use of the King James Bible. If you claim some measure of scholarship and cannot read it, I am afraid of you. I’m no genius, but I can read the 1611 King James Bible. I use it in research, and have read it once from Genesis to Revelation. If a so-called Bible teacher is not educated enough to read a 1611 KJV, then he is not educated enough to lecture folks about texts and translations of the Bible.

However, there are sincere folks who might want to read the 1611 King James Bible, but struggle with the typography, spelling, etc. It has some variations from modern English printing that may initially be off-putting. Understanding these variations before beginning will remove some of the difficulties. Perseverance will remove many of the rest. Below I will give some visual samples from (as well as links to) pages of a 1611 Bible printed by the Kings printer, Robert Barker.

1611 Bible typeface

A typeface is a particular set of characters (alphabet, numerals, punctuation, etc.) that share a common design. In modern times, we often think in terms of “font.” Font is a specific size and style of a particular typeface. In Microsoft Word, Old English Text MT will produce a typeface similar to the typeface used in the 1611 translation.)

The 1611 Robert Barker printing of the new Bible translation uses three different types. The Bible translation itself is blackletter typeface. Blackletter is sometimes referred to as Gothic script or Old English, but it is not a typeface limited to English. It was common in the western European countries, and remained the popular typeface in Germany, Norway, and Sweden long after it had gone out of style in England and the United States.

Roman type

The dedication, preface, chapter headings, summaries, genealogies, etc. are in roman type (and some italic), providing an intriguing visual distinction between the text of the Bible and its related materials. The first letter in each chapter is a very large roman letter. Illustration 1 shows large and small roman type used in the preface, “The Translators to the Reader.”

Illustration 1. Translators to the Reader.

Blackletter type

The text of the 1611 Bible is printed in blackletter type, and added target language words are in smaller roman type. These represent words that were added by the translators to more understandably translate from the source languages (Hebrew, Aramaic, Greek) into the target language (English). For examples, see the word “and” in Illustration 4, as well as “are” and “to bee” in Illustration 7. (When printers began to set the King James Bible in roman type instead of blackletter, italics were used to distinguish the added words, as appears in our modern printings of the KJV.) This was explained by Samuel Ward to the Synod of Dort, thusly:

“Sixthly, that words which it was anywhere necessary to insert into the text to complete the meaning were to be distinguished by another type, small roman.” Reported by translator Samuel Ward to the 1618 Synod of Dort

Illustration 2. John 19:19

Illustration 2 shows the blackletter type in the first part of John 19:19, followed by small roman type. The superscription placed over the crucified Messiah is furnished in roman type and in all caps (Matthew 27:37; Mark 15:26; Luke 23:38; John 19:19). See Illustration 2. Notice also in the John 19 example above, that when “U” is capitalized, even within a word, it appears in the “V” style. These (u & v) are not two distinct letters in this Early Modern English blackletter typeface of the King James Bible.

Small roman type is used in the New Testament at least twice to designate a phrase found in the Greek text from the Syriac (or Aramaic) language: Eli, Eli, lama sabachthani (Matthew 27:46, but not in Mark 15:34), and Talitha cumi (Mark 5:41).

Italic type

Various places in the explanatory materials use italic type, including the introductions, as well as in the marginal references to more literal translations, and the alternate readings.

1611 Bible alphabet

The letter i

There is no “J” or “j” in the 1611 English Bible, only an “I” or “i”. The capital “I” looks much like the later capital “J”. That is a stylistic flourish, however, rather than a different letter. The “j” look also appears as an extended ornamental flourish, as on the letter “i” at the end of Roman numerals. For example, XXIIJ or xxiij is Roman numeral 23.

Illustration 3. “I” flourish in 1 Kings Chapters 13-14

Illustration 4. Genesis 24:1

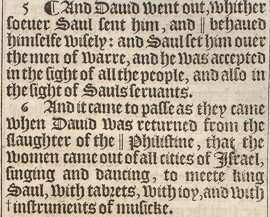

Illustration 5. 1 Samuel 18:5-6

1 Samuel 18:5-6 in Illustration 5 exhibits several traits of printing style of the 1611 Bible, including the capital “I” in Israel. Notice also, (1) the capital “S” in Saul, (2) the lack of apostrophe in “Sauls servants”, (3) some symbols for marginal readings, and (4) at the beginning of verse 5 there is a pilcrow (⸿, a character marking the start of a paragraph).

The letter r

Illustration 6. Rounded “r”, Ephesians 1:6-7

The rotunda or rounded r (ꝛ) is a stylized “r”, probably used by printers to save space. In the example from Ephesians 1:6-7 (Illustration 6), both types of “r” are used, the regular “r” and the rounded “r”. In verses six and seven, “ꝛ” is found in the words “praise”, “glorie”, “through”, “forgivenesse”, and “according”. The regular “r” is found in “grace”, “wherein”, “redemption”, “riches”, and “grace”. The rounded “r” (ꝛ) follows letters with curved strokes – “p”, “o”, and “h” in this example (and a “w” in Illustration 2). Other than style, it is no different than the regular “r”. The regular “r” always begins words (i.e., when “r” is used as the first letter). A 1611 capital “R” is seen in the word LORD in Illustration 4.

The letter s

The small letter “s” comes in two forms. The long “s” ( ſ ) letter looks similar to “f” letters, and is often so confused by modern readers. The long “s” is a small letter “s”, either at the beginning of a word or used internally within a word. The capital “S” looks different (see Illustration 5), as well as the short “s” letter used when “s” is the last letter of a word (which, interestingly, is also a trait of the Greek sigma, σ and ς. See Illustration 7, “sonnes” in verses 18 and 19). A short or round “s” is always used at the end of a word ending with “s”, and possibly sometimes used when the letter “s” is adjacent to a letter “f” (though this was not true in the examples I checked, “satisfaction” in Numbers 35:31-32, “satisfied” in Isaiah 53:11, “offspring” in Acts 17:28-29).

Illustration 7. Genesis 9:16-20

The words “five” and “second” (et al.) in Genesis 7:11 (Illustration 8, below) depict how easily the “f” might be confused with a long “s” (ſ), and vice versa.

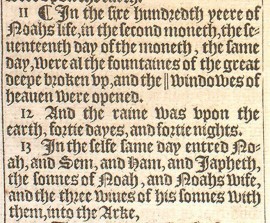

Illustration 8. Genesis 7:11-13

Several points are demonstrated in Illustration 8, this snip of Genesis 7:11-13. The pilcrow is used. There are no apostrophes (’) to show possession, as we punctuate modern words. Notice “Noahs life” in verse 11 and “Noahs wife” in verse 13. Verse 13 gives an example of the capital “S” beginning the name “Sem”, as well as the use of the long “s” and short “s” in the word “sonnes”. “Iapheth” shows how the capitalized “I” looks quite like a modern “J” (though it is not).

The letter u

The “u” and “v” are interchangeable letters, according to their placement in a word. When it is the first letter of the word, “v” style is used. When within the word, “u” style is used. “V” is used when the letter is capitalized (See Illustration 2). However, the capital “U” in blackletter appears more like what we modern readers might think of as a “U” rather than “V” (nevertheless, it is one letter).

In some roman type “w” is a double u (that is, two of them side by side, and the “u” usually appears like a “v” – thus “vv”, – vvhen, vvhere, etc.). I do not believe this type printing occurs anywhere in the 1611 King James Bible.

The letter z

In the 1611 blackletter type, the small letter “z” appears somewhat like a cursive “z”, but does not extend well below the line (z). For example, see Uzziah in 2 Kings 15:13, 30, 32, 34.

The letter þ (called thorn)

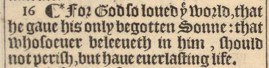

Illustration 9. John 3:16

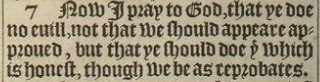

A “y” (i.e., what appears to be one), when used with a superscript “e” (i.e., above the “y”, yͤ; see Illustration 9.) or in an abbreviation “yt” (yͭ, for “that” as in 2 Cor. 13:7), represents the Old English letter “thorn” (þ). In those cases, the “y” works as a “th” sound rather than “y”. It means “the” (not “ye”) and “that” (not “yet”). The word should not be confused with the second person plural pronoun “ye” (and it is pronounced with a “th” rather than “y” sound). This usage can be found in a number of places, such as in 1 Kings 11:1, Job 1:9, Ezekiel 32:28, John 3:16; 15:1, Romans 15:29, Colossians 1:1, and James 3:12. Illustration 10 shows the abbreviation “yt” (yͭ) for “that”. Other cases of “yͭ” include Jeremiah 49:17; John 12:2; Hebrews 7:21.

Illustration 10. 2 Corinthians 13:7

The letter æ (called ash, Æ æ)

This letter is used at least three times in the 1611 Bible, in the words Ænon (John 3:23) and Æneas (Acts 9:33-34).

In Modern English orthography, both the thorn (þ) and ash (æ) are obsolete. Though the æ occasionally appears in words like encyclopædia, it is not now considered a letter in the English alphabet. Technically, though not obviously, the use of þ (thorn) can still be seen in signs such as “Ye Olde Tavern” (meaning “The” Olde Tavern, though most readers may not realize it). 1611 Bible symbols

Abbreviations

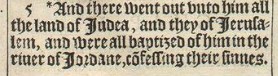

Illustration 11. The tilde abbreviation, Mark 1:5

A tilde or macron (~ -) is used in some words as a sort of abbreviation. An “m” or “n” following a vowel may be replaced by placing the tilde or macron over the vowel, as cõfessing in Mark 1:5. This is the equivalent of “confessing,” abbreviated. This usage probably was a printer’s decision, to save space; compare Matthew 3:6 where it is confessing rather than cõfessing. See also Acts 13:30, which shows the omission may also be at the end of a word – “frõ.” “yͤ” abbreviates “the” and “yͭ” abbreviates “that”. In 2 Chronicles 23:21 “wt” abbreviates “with”.

Marginal notes

Illustration 12. Isaiah 53:5-6

These two verses in Isaiah 53 in Illustration 12 show three different symbols used to lead to marginal notes: asterisk, cross or dagger, and double bar (*, †, ||). The asterisk (*) denotes a cross reference to a related scripture or scriptures. The cross, or dagger, (†) indicates a more literal translation (prefaced by Heb., Chal., or Gr., followed by a word or words in italics).The double bar (||) points to an alternate reading (|| Or, followed by a word or words in italics).

Miscellaneous

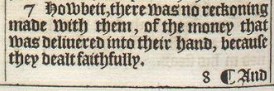

Illustration 13. Catchword under 2 Kings 22:7

At the bottom right of pages in the 1611 Bible, you will find a “catchword.” A catchword is a word placed at the right-hand foot of the page that anticipates (records or repeats) the first word on the following page. See Illustration 13. This was common in early printed texts up into the 18th century. It probably helped both the printer and the reader to make the connection between the two pages.

While there are no apostrophes of possession, there is at least one place it is used to form a contraction. An apostrophe replaces the “e” in “long wing’d” in Ezekiel 17:3.

Hyphens come in two styles – within words, the single dash “-” (e.g. Iehouah-ijreh, Genesis 22:14; Nebuchad-rezzar, Jeremiah 21:2, 7) versus a double dash “⸗” for a hyphen dividing a normally unhyphenated word at the end of the line of type (see Illustration 6, “accep⸗ted” in Ephesians 1:6).

The conjunction “and” is often abbreviated or brevigraphed (represented) with a form of the Tironian “et” (see examples in Genesis 2:4, 7, 22, 25.)

In Genesis, “LORD” for Jehovah is in all caps (LORD), but in small caps (Lord) in other books of the Bible. Unexpected capitalization sometimes emphasizes or calls attention to a verse or something within it. All roman caps accentuate an inscription, or something written, in Daniel 5:25 (+ vs. 26-28); Matthew 27:37; Mark 15:26; Luke 23:38; John 19:19; Acts 17:23; Revelation 17:5; Revelation 19:16. In addition, I AM THAT I AM in Exodus 3:14 appears in all caps in blackletter type. Exodus 6:3 has IEHOVAH in all roman caps.

In the 1611 Bible, there are no quotation marks (“ ”) for dialogue, quotes, etc. If you use a modern KJV printing, this is the same, not a difference. Some of these typographical or orthographical traits may be seen continuing much later and even in printings in roman type, such as the long “s” and the “i” instead of “j”.

1611 Bible words

Extended discussion of Bible words is too cumbersome to include here. (A little information about thees and yes is here and about verb endings here.) In 1611, English spelling was not standardized to the point is has now developed. Therefore, a number of variant spellings appear throughout the 1611 printing. An “e” word ending that has dropped out of use is a very common trait. Nevertheless, it should be rare that the average reader cannot discern what the word is, despite the variant spelling. The sound of the word is often the same or very similar.

A few examples

- beleeveth = believeth

- crosse = cross

- doe = do

- euery = every

- fortie = forty

- iniquitie = iniquity

- layd = laid

- moneth = month

- onely = only

- owne = own

- riuer = river

- shalbe = shall be

- sonne = son

- warre = war

- windowes = windows

- yerre or yeere = year

Final notes

You can view and examine for yourself a digital image of a 1611 printing of the Bible. Here is one online option:

In addition to online images, facsimile reprints are also available. Kings printer Robert Barker made several printings of the new translation, some of which may vary slightly from the visual examples I give. If you find something that is slightly different, do not be surprised.

I am not advocating that one must read the 1611 printing of the King James, but rather offering some advice to those who want to do so. There is also an accommodation for those wishing to read the 1611 Bible while avoiding the blackletter type. A Bible reprint is available in print of the original 1611 except that it is set in roman type rather than blackletter. (It may or may not be available online.) Also, there is a “modernized” Online Blackletter Edition which “give(s) the reader a feel for the original 1611 King James Bible” without including “all the typographic representations found in the original.”

I do not claim any expertise, just learning by trial and error (including what others said about these trials and errors). I may have gotten some minor details wrong, or I may have left off something I should have addressed. (If you notice something that needs to be addressed, let me know.) This kind of stuff intrigues me, even when only in relation to the English language and its history. I hope this essay might benefit someone, and not just about quirks in our language – but most especially regarding the Bible. May the Lord bless you.